Safe Routes Partnership deputy director visited Tokyo to examine their walk to school practices

Safe Routes Partnership deputy director, Margo Pedroso, visited Tokyo in May 2011 to examine their walk to school practices. The visit was made possible through the vision of Leonard J. Schoppa, professor of politics at the University of Virginia and a grant from the Japan Foundation. Below are Margo’s observations. Photos are ©2011 Skye Fitzgerald.

Japan is a world away when it comes to walking to school. Just 1.7% of Japanese children ride the bus to school, and children walk to school in groups, unaccompanied by their parents—even first graders. Japanese law requires that elementary schools be sited so that all children served live within no more than 2.5 miles.

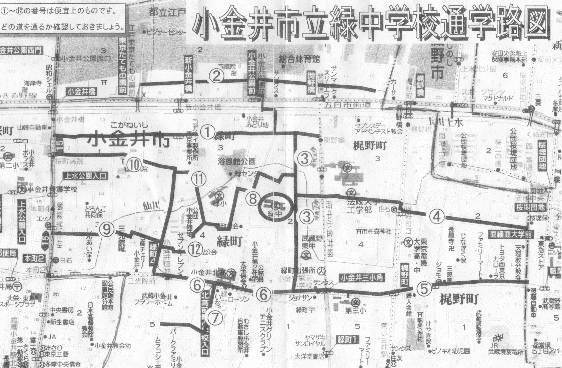

School PTAs produce annual safety maps of the school neighborhood with recommended routes to school, and work with city offices to fix any hazards. The PTAs ask retired adults to come outside and keep an eye on the walk to school, and children can ask for help at dozens of “safe zone” houses. Many schools have “school zones” which are closed to vehicular traffic during school commutes.

Parents we met on our trip said walking to school is a basic principle of Japanese life, and that their roads cannot accommodate the traffic that would result from driving to school. They value their children learning how to navigate their neighborhoods and be independent. Parents also noted that when everyone walks, it is the safest because there is no mixing of cars, bicycles and pedestrians in small spaces.

While Japan and the United States have many differences that affect the trip to school, there are some lessons we can take away from Japan’s system:

- Japan’s higher population density and shorter distances make walking to school more feasible, but their school siting policies are what really make the difference. School siting policies in America should examine the school site’s proximity to the student population and the impact on levels of walking, bicycling, driving and busing.

- Japanese parents are also very concerned about “stranger danger.” But they manage that fear by near-universal participation in PTA efforts to create “eyes on the street” and safe routes for children to walk to school. In communities where more parents are working and unavailable, retired adults step up to fill the gap in watching out for children. Engaging more retirees could be an opportunity for U.S. Safe Routes to School programs.

- In Japan, all children are taught safe walking skills in kindergarten, and practice those skills walking to school in groups. In junior high, students learn to take the transit system and navigate other neighborhoods. In the United States, children would benefit greatly from having bicycle and pedestrian skills built into their curricula.

- Finally, the Japanese system clearly demonstrates the “safety in numbers” phenomenon. Because hundreds of children walk to school at the same time, they are very visible to drivers. And, because it affects so many children, pedestrian safety is a priority for parents, retired adults, the schools and local government. Perhaps our collective Safe Routes to School efforts can reach a similar tipping point.